Another manner of treason: The trial and execution of Catherine Bevan in New Castle, Delaware

On September 10, 1731, in New Castle, Delaware, 50 year old Catherine Bevan and Peter Murphy, a young servant, were executed for the murder of Catherine’s husband Henry Bevan. Peter was hanged, but Catherine had been sentenced to death by burning. The executioner had planned to hang her over the fire so that she would be strangled to death before the flames reached her, but he had never executed someone by burning before and lit the fire too soon. The flames leapt up, burning the rope around her neck so that she fell alive into the fire and was burned to death.

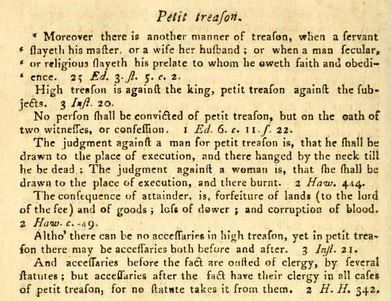

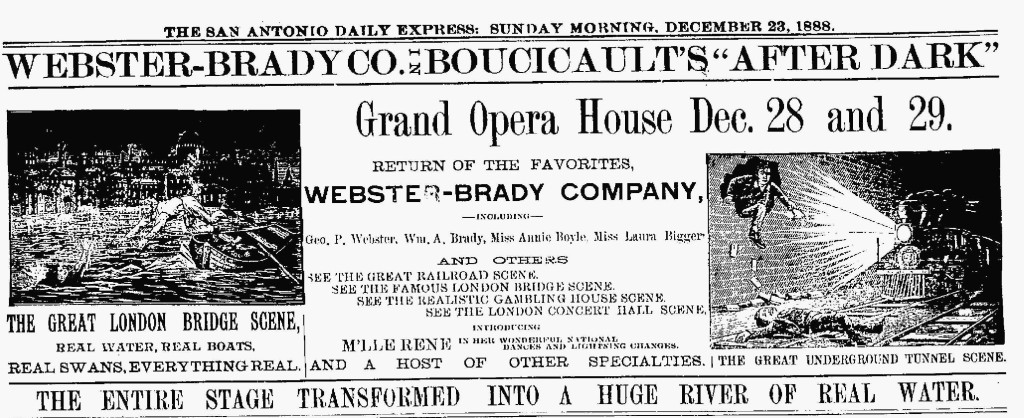

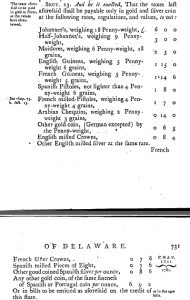

A description of petty treason from Conductor Generalis, an 18th century manual for justices of the peace in the American colonies.

The murder had happened in June of 1731. Henry Bevan had complained to neighbors that his wife and servant mistreated him and the neighbors gossiped about Catherine and Peter’s relationship. When Henry died suddenly and was nailed into his coffin before anyone could view the body, the local magistrate became suspicious and had it pried open. The body was covered in bruises. Catherine and Peter were brought in for questioning and Peter quickly confessed. He said they had first tried to poison Henry by spiking his wine with sulfuric acid. When that didn’t work, Peter beat him until he was weak enough for Catherine to strangle with a handkerchief. Peter changed his story on the scaffold, saying that Catherine hadn’t taken part in the murder, but that it had been her idea. Catherine steadfastly denied everything, even at her execution.

Catherine Bevan was the only woman executed by burning in Delaware and the only woman ever burned for murdering her husband in colonial America. But why was Catherine Bevan burned while her co-defendant was hanged. And how common was execution by burning in colonial America?

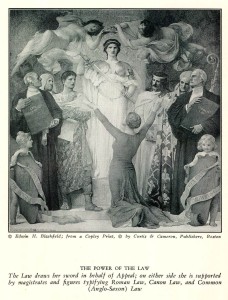

Both Bevan and Murphy were convicted of petty treason, a crime brought to the American colonies from English law. The English Treason Act of 1351 (25 Edw. III St. 5 c.2.), besides the usual forms of treason like adhering to the King’s enemies, also defined “another manner of treason,” murdering someone to whom, in medieval society, you owed obedience. The 1351 Act named three types of murder that qualified as petty treason: a servant slaying his master, a wife slaying her husband, or a man secular or religious slaying his prelate. Petty treason was originally punished the same as treason. A convicted man was hanged, drawn and quartered, while a woman was burned to death. Eventually hanging, drawing and quartering was considered too cruel and the punishment for men was changed to hanging, but the punishment for women remained burning.

The English colonies in North America for the most part adopted English laws on petty treason. Delaware is a good example of how this worked. In 1719 the Delaware General Assembly passed a law providing that all capital crimes in Delaware were to be tried and punished the same as in England (1 Del. Laws 64). The law was somewhat confusingly worded and in 1741, ten years after Catherine Bevan’s execution, a supplemental act was passed to clarify “That every person or persons, who shall be guilty of any petty-treason, misprision of treason, murder, manslaughter, homicide, bestiality, incest or bigamy, shall be tried in like manner as other felons by the said act are directed to be tried, and punished in the like manner as persons guilty of the like crimes and offences are punishable by the laws and statutes of that part of Great Britain called England.” (1 Del. Laws 225)

Other colonies adopted burning as a punishment for petty treason as well, but it was not always applied. At least two other women in colonial America were executed for murdering their husbands, but were hanged not burned. In 1644 a Maine woman named Cornish was hanged for murdering her husband and in 1708 Connecticut hanged Abigail Thompson for the murder of her husband. There is very little information available about the 1644 Maine case. As far as I can tell, Connecticut never adopted English criminal law as a whole and had no laws on petty treason, which may account for the punishment in that case.

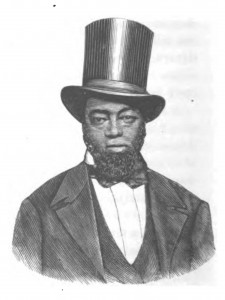

By far the women most commonly convicted and burned for petty treason in the North American colonies and the early United States were those falling into the first category of petty treason, “a servant slaying his master.” Enslaved women convicted of killing their owners, taking part in slave revolts, or committing arson were commonly executed by burning. I have been able to find mention of 24 women executed by burning in early America; 22 of them were enslaved women. Enslaved women were executed by burning in many states, New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts as well as the South. The one other woman executed by burning in colonial America was a white servant in Maryland, who assisted her fellow servants in killing their employer.

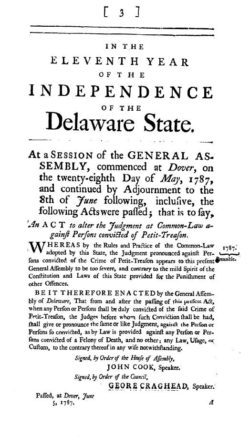

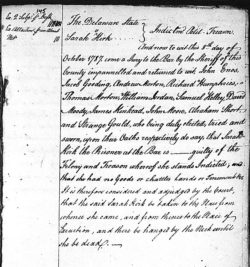

Catherine Bevan would be the only woman burned in Delaware. Nearly 60 years later, on April 15, 1787, a woman named Sarah Kirk, living in Christiana Hundred, struck her husband James in the head with a stone and then beat him to death with a stick. Not wanting to repeat the botched 1731 burning, the state moved relatively swiftly to change the law. On June 5, 1787 the General Assembly passed a law (2 Del. Laws 905) changing the punishment for petty treason to hanging, the same as for any other “felony of death.” Sarah Kirk’s trial was held on June 6th. She was found guilty of petty treason and sentenced to be hanged. In what may have been an excuse to make sure the new law had gone into effect before the trial, her attorney asked that her conviction be overturned because one of the jurors had not sworn the oath of fidelity to the state. The conviction was set aside and she was retried on October 5th, 1787. She was once again found guilty and sentenced “to be hanged by the neck until she be dead.” Sarah Kirk was executed in New Castle on October 12th where, according to a newspaper account, “she behaved with those sentiments of penitence and resignation, which became her unhappy situation.”

The punishment of petty treason by burning was abolished in England in 1790 and gradually abolished in the United States during the late 1700s and early 1800s. The specific crime of petty treason was also abolished and was treated as any other type of murder.

Sources:

David V. Baker, Women and Capital Punishment in the United States: An Analytical History. McFarland, 2015.

Ruth Campbell, Sentence of Death by Burning for Women, 5 J. Legal Hist. 44 (1984)

Matthew Lockwood. From Treason to Homicide: Changing Conceptions of the Law of Petty Treason in Early Modern England, 34 J. Legal Hist 31 (2013)

The records of the Catherine Bevan trial are unfortunately missing but the records from State v. Kirk are available at the Delaware Public Archives.

Pennsylvania Gazette (June 1731)

Pennsylvania Gazette (Sept. 23, 1731)

This week’s Game of Thrones episode has put the medieval practice of

This week’s Game of Thrones episode has put the medieval practice of