The fabulous Springer fortune of Wilmington Delaware

In 1883, two men, George W. Ponton and Charles H. Bierce were arraigned in New York on charges of larceny. They had persuaded a third man, Charles W. Van Dorn, to loan them $200, which would be repaid when Bierce came into a fortune of $90,000. Bierce claimed to be one of the Springer heirs, descendants of Charles Christopher Springer, an early settler of Wilmington, Delaware. Springer, it was said, had owned a large portion of the land where the city of Wilmington now stands, which he had leased to Old Swedes Church, which in turn leased it to the city of Wilmington for 99 years. The lease was now up and soon the city would settle with the heirs for 20 million dollars. There was, of course, no fortune and Van Dorn never got his $200 back. But the story of the fabulous Springer fortune waiting in Wilmington lived on for almost another hundred years, as fortune hunters, confidence tricksters and honestly hopeful people named Springer organized associations, collected money, and badgered Wilmington officials in a futile effort to claim the untold millions waiting for them.

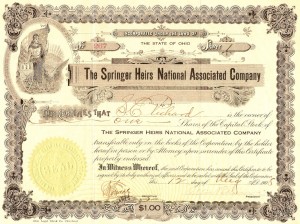

The quest for the mythical Springer fortune seems to have begun in the 1870s when J.N.W Springer and David Gillespie formed the Springer Heirs Association, to raise money to investigate the claim to the estate. It was probably inspired by earlier very similar claims in the 1830s and 1840s involving property in Manhattan owned by Trinity Church (Bogardus v. Trinity Church, 4 Paige Ch. 178 (1835) and Humbert v. Trinity Church, 24 Wend. 587 (1840)) and the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, one of which actually went to the U.S. Supreme Court (Harpending v. Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of City of New York, 41 U.S. 455, 10 L. Ed. 1029 (1842)) The fact that the heirs lost in all of these cases doesn’t seem to have deterred the Springers.

All through the 19th and into the 20th century the search for the fortune continued, with the size of the prize growing every year. Springer’s supposed property grew from encompassing a part of Wilmington to the entire city, and to include the site of the DuPont gunpowder mills for good measure. Charles Springer was said to have been a Swedish baron who had a fortune hidden away in a Swedish bank, or walled up in a hidden building, or possibly buried in a tomb. Con artists offered to sell Springer’s will for large amounts of money, lawyers spent years in Europe doing research at the heirs’ expense, and the presidents of various Springer heirs associations collected money which was mostly spent on hotels while traveling the country and collecting more money. So many people contacted Wilmington officials asking about the fortune, that the city was forced to print pamphlets denying the story.

Newspapers across the US added to the confusion by printing inspiring stories about the ordinary people who were possible heirs, including two manicurist sisters in San Francisco, a kidnapped child in California and a railroad yardmaster from Reno. Only the Wilmington papers expressed any skepticism about the story, generally portraying the heirs as hopeless suckers and pests.

Interest in the Springer estate seems to have died down now, except for a few mentions on genealogy websites, but similar hoaxes continue. In 2001, the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals decided a case in which the Pennsylvania Association of Edwards Heirs (who claim their ancestor was the rightful owner of a large portion of lower Manhattan) sued Wachovia Bank after nearly 1.5 million dollars in association dues had been squandered by the officers of the association. Pennsylvania Ass’n of Edwards Heirs v. Rightenour, 235 F.3d 839 (3d Cir. 2000). The heirs lost.