Weird laws, blue laws, Delaware laws

It’s time for another look at the weird laws of Delaware. This time I’m taking a look at what you can and cannot do on Sunday in Delaware. You may have seen this cited on the internet as a weird Delaware law:

Delaware prohibits horse racing of any kind on Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

Status: True

Yes it’s true, Title 28, section 906 of the Delaware Code reads, “There shall be no horse racing of any kind on Good Friday or Easter Sunday.” You might think that this is just an old law that was accidentally left on the books, but it was only passed in 1973 (59 Del. Laws 1973, ch. 25, § 1), and is actually a liberalization of the state’s earlier law which banned horse racing every Sunday.

Horse racing was just one of the many activities that used to be banned in Delaware on Sundays. Laws reserving Sunday as the Sabbath and a day of rest were brought to the American colonies from England and existed in all of the original colonies. They were commonly called “blue laws.” Interestingly, no one seems to agree on why, it may have been because they were originally printed on blue paper, or possibly, because the Puritans and their strong religious scruples were often called “blue” as in “bluenose.”

Delaware’s early Sunday laws were strict but typical of their time. The 1852 Delaware Code prohibited the performance of “any worldly employment, labor, or business, on the Sabbath day (works of necessity and charity excepted)…” Delaware law also prohibited leisure activities such as “fishing, fowling, horse-racing, cock-fighting, or hunting game” on Sundays, as well as assembling to “game, play or dance.” (Revised Statutes of the State of Delaware chap. 131, sec. 4 (1852))

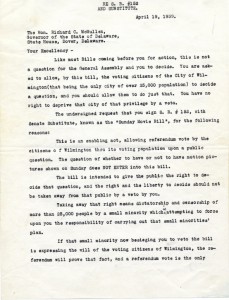

A 1939 petition to the Governor of Delaware, asking him to support a referendum allowing movies to be shown in Wilmington on Sundays.

By 1953 the Delaware Code no longer banned all work on Sundays, but still banned horse racing, along with auctions, dances, theatrical performances and motion pictures, at least in unincorporated areas. Incorporated areas were permitted to make their own rules, but these activities could not be held before noon or between 6 PM and 8 PM. Also banned on Sunday was barbering (24 Del.C. (1953) § 415) but, curiously, not ladies hairdressing, which eventually led to a Delaware Supreme Court case which held that the law was “… an unjust and unreasonable attempt to discriminate against this class of persons [barbers]; that its effect is not to benefit the interests of the public; and that it constitutes an arbitrary interference with private business.” Rogers v. State, 57 Del. 334, 339, 199 A.2d 895, 897 (1964)

Sunday closing laws as a whole were never found unconstitutional and have been upheld by the United States Supreme Court. (McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961), Gallagher v. Crown Kosher Super Mkt. Inc., 366 U.S. 617 (1961), Two Guys v. McGinley, 366 U.S. 582 (1961), Braunfeld v. Brown, 366 U.S. 599 (1961)) Many states in the U.S. still have restrictions on Sunday activities.

Currently in Delaware besides the ban on horse racing on Good Friday and Easter Sunday, liquor can only be sold on Sundays between 12:00 noon and 8:00 p.m. (4 Del. Code § 709) (with some exceptions for small wineries, distilleries and breweries), hunting is prohibited on Sunday (except fox hunting with dogs) (7 Del. Code § 712), taking shellfish for commercial purposes (with some exceptions) is prohibited (7 Del. Code § 1904), “adult establishments” must be closed, (24 Del. Code § 1625), and you can’t use drifting gill nets until after 4 p.m. on Sunday (7 Del. Code § 923). Luckily for me it’s not illegal to write blog posts on Sundays.

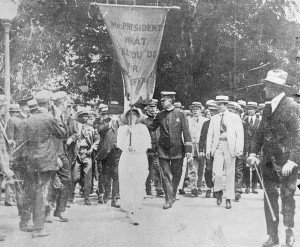

UPDATE: The story of how 500 people were arrested in one day and the Delaware blue laws were finally repealed.

Photo credits:

Delaware Public Archives. Delaware in World War II Collection. http://cdm15323.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p15323coll6,10024

For more information on blue laws see:

Neil J. Dilloff, Never on Sunday: the Blue Laws Controversy, 39 Md. L. Rev. 679 (1980)

Lesley Lawrence-Hammer, Red, White, but Mostly Blue: The Validity of Modern Sunday Closing Laws Under the Establishment Clause, 60 Vand. L. Rev. 1273 (2007)